ARTICLES

LETS TALK BREATHLESSNESS: Why it happens, what it really means, and how to build fitness that actually lasts.

Grant Taylor

16/02/2026

AN ARTICLE BY GRANT TAYLOR

If you are noticing that you get out of breath sooner than you ever did before, you are not imagining it. Stairs feel steeper, classes feel quicker, even a short hill can get the heart racing. Most people blame fitness or lifestyle, however the real reason usually comes from normal, age related changes within the body that influence how effectively you breathe.

One of the first changes is the flexibility of the heart. As we age, the heart has to work a little harder to move the same amount of blood. When it needs more effort, it beats faster and as a result your breathing speeds up. This can feel frustrating, especially when it happens during light effort, however it is not a permanent limitation. The heart is a muscle and responds well when challenged. Interval based cardiovascular work or classes that push your breathing slightly will improve the heart’s resilience, increase capacity and make everyday movement feel easier.

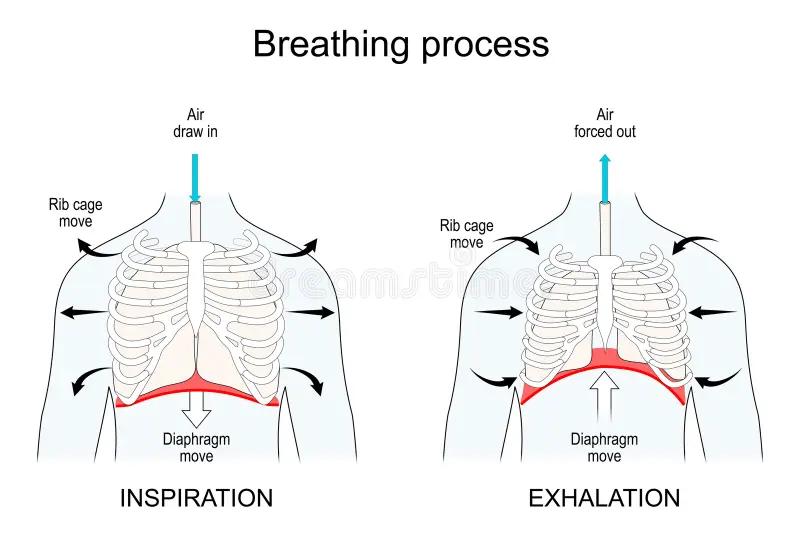

The ribcage is another major player in how well you breathe. Most people think of breathing with the belly or lifting the shoulders, but the ribcage is the structure that dictates how well air actually moves. When you inhale, the diaphragm contracts and pushes into the ribcage. The ribs are meant to expand in all directions, with the lower ribs moving the most and the movement gradually decreasing higher up. If the ribs do not expand well, you simply will not take in much air.

Exhalation is equally important. As you breathe out, the ribs should compress and drop slightly. This inward motion pushes air out and creates space for the next breath in. If your exhalation is weak, your inhalation will be limited. Place your hands around your ribs and you can feel this expansion and compression for yourself.

With age, we lose some mobility in the joints where the ribs attach to the spine. This stiffness restricts rib movement, the diaphragm has to work harder, and breathing becomes less efficient. The good news is that the ribcage responds quickly to movement. Thoracic rotation is especially effective. So is hands behind head breathing, which forces the ribcage to expand properly. Just a few minutes a day can improve rib mobility and breathing efficiency.

Breathlessness is also influenced by carbon dioxide. The urge to breathe is triggered by rising CO₂, not falling oxygen. As CO₂ rises, the body sends a signal to inhale. Many adults become more sensitive to this signal over time, especially if they breathe through the mouth or breathe in a shallow pattern. You can retrain this sensitivity.

A simple way to measure it is the BOLT test. Sit comfortably and breathe through your nose. After a gentle exhale, pinch your nose and time how long it takes until the first natural urge to inhale. You are not testing breath holding ability, you are measuring sensitivity to CO₂. Ten to twenty seconds is common at first. Twenty to thirty is solid. With practice, thirty five to forty five seconds is achievable.

You can build CO₂ tolerance during everyday walking. Breathe through your nose, then after an exhale hold your breath for five to ten seconds, take a couple of calm breaths and repeat. As you improve, you can hold between lampposts. This trains the body to handle rising CO₂ more comfortably, which directly reduces that breathless feeling.

With consistent practice, these strategies make your breathing calmer, your movement more resilient and your daily activities easier. Small adjustments, applied consistently, create meaningful change.

Be The First To Comment